Children and their parents make up a significant part of the population seeking asylum in the UK, but this receives limited attention in public discourse. Ilona Pinter draws on the UK government’s data, alongside additional research, to explore how children and families are being affected by the growing asylum backlog and the increasing use of immigration detention.

In recent weeks there has been increased media and public attention on the immigration detention and accommodation of individuals and families arriving in the UK by small boats – over 40,000 arrivals in 2022 so far, according to official reports.

Aside from the obvious fact of dangerous crossings, one of the biggest policy challenges currently is the huge asylum backlog, which has quadrupled in the last five years from 29,522 individuals waiting for an initial asylum decision in December 2017 to 122,206 in June 2022.

As a result of this backlog, more people are remaining in the asylum system for longer, requiring Home Office accommodation and support. Analysis last year showed that the length of time people were receiving Asylum Support had increased in recent years. At the end of 2017, 46% of cases were receiving Section 95 – the main form of support for those awaiting an asylum determination – for over a year. At the end of 2020, this was up to 73%, with 8% of cases remaining on support for over five years. There is also a shortage of suitable accommodation for new arrivals, leading to over-reliance on temporary hotel accommodation and increasing use of immigration detention.

Among those affected are children who make up a quarter of all asylum claimants and dependents in the UK. This week, we approach the one-year anniversary of the largest single loss of life in the English Channel since 2014, when Hadia, Mubin, Hasti and their mother Khazal, alongside 28 others, drowned while trying to reach safety in the UK in November 2021. As Home Office quarterly statistics due on 24 November 2022 will undoubtedly show, many more children have crossed the channel by small boat since. This blog post considers some of the government’s own data, alongside other evidence, to highlight how children and families are being affected by the asylum backlog and increased use of immigration detention.

Small boat arrivals

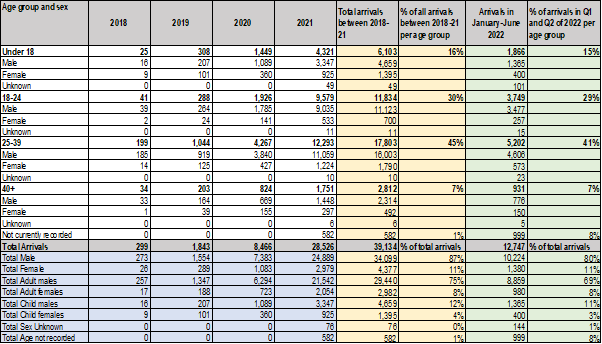

While 69% of small boat arrivals in the first half of 2022 were ‘adult males’ (down from 75% of arrivals between 2018-21), many of them will be part of a family, including fathers and adult children. In addition, significant numbers of women and children are also making dangerous crossings due to a lack of safe and legal routes. The Home Office published statistics citing 12,747 small boat arrivals in the first half of 2022 (Figure 1), of which 1,866 (15%) were children. Between 2018 and 2021, 6,103 children (16%) were recorded as having arrived by small boat.

Figure 1: Small boat arrivals between 2018 and 2022, based on author’s analysis of Home Office Irregular Migration Statistics for year ending June 2022.

These data do not differentiate between children who arrive on their own as unaccompanied children and those who arrive with their families. However, other Home Office data show that over the last decade, accompanied children made up 16% of all asylum applicants and dependents (60,677), and a further 7% (25,759) were recorded as unaccompanied child claimants.

Children entering immigration detention

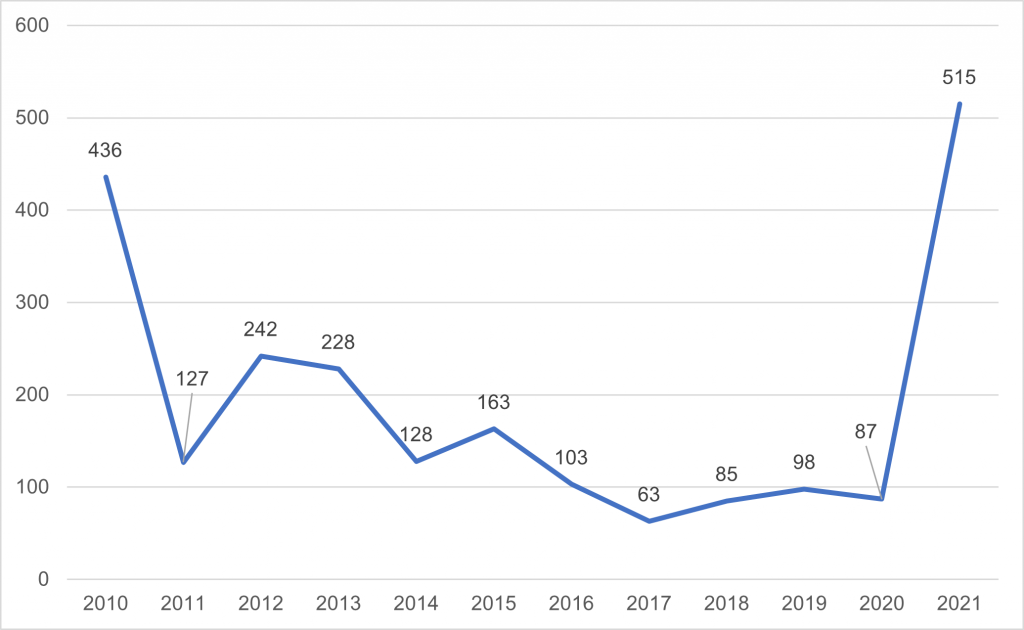

We have also seen a huge increase in the numbers of children being detained. In 2021, 515 children entered immigration detention – a staggering 492% increase from 87 children in the previous year (see Figure 2). According to Home Office data, 454 children (88%) arrived in the UK via small boats. The figures could be higher since not all detention facilities are listed in published statistics. An HM Prisons Inspectorate report on the Western Jet Foil, Lydd Airport and Manston short-term holding facility in Kent, which detains individuals and families arriving by small boats, revealed that 40 children had been detained there between April to June 2022, five of whom were unaccompanied. These figures are not currently part of published statistics. Worryingly, more children entered immigration detention in 2021 than in 2010 when the government changed its policy to stop routinely detaining large numbers of children.

Figure 2: Numbers of children under 18 entering immigration detention, based on author’s analysis of Home Office quarterly immigration statistics for year ending June 2022.

Figure 2 numbers include children detained with their families as well as unaccompanied children who have been wrongly assessed as adults. As past research and inspection reports have shown, immigration detention is incredibly damaging for children even for short periods of time. We have already heard about violence, drug selling, a diphtheria outbreak and mistreatment of detainees at Manston through news reports and testimonies from detainees.

Accommodation challenges

Alongside detention, there has been a significant increase in the use of contingency accommodation, predominantly commercial hotels. At the end of 2021, 26,380 people were accommodated in hotels – more than twice as many compared to the previous year. Children made up 10% (2,569) of these as the number of families in hotels has continued to increase. Alongside poor nutrition and serious welfare challenges due to a lack of access to cash, hotel stays have also meant children have been missing out on vital education, access to healthcare (including routine immunisation programmes) and developmental opportunities.

Grave concerns have also been raised by advocates, politicians and statutory agencies about the failures in safeguarding unaccompanied children who have been accommodated in Home Office-run hotels since 2021, instead of local authority care in line with statutory duties. Last month Ministers admitted to not knowing the whereabouts of 222 unaccompanied children who have gone missing from placements. In November 2022 there have been reports of at least four sexual assaults on children left unaccompanied in hotels, including rape. Separately, a child wrongly assessed as an adult was stabbed in a hotel.

Increasing duration of the asylum process

The length of time that children and families are spending in the asylum process is also increasing as a result of policy changes. The Inadmissibility Process was introduced in 2021 to facilitate removals to so-called ‘safe’ third countries. The first of the government’s partnerships has been with Rwanda. Unaccompanied children are protected from the Inadmissibility Process unless they are wrongly assessed as adults. Meanwhile families with children, though not a priority for Rwanda removals, are not protected, and worrying reports in Spring 2022 suggested accommodation providers were preparing for child arrivals.

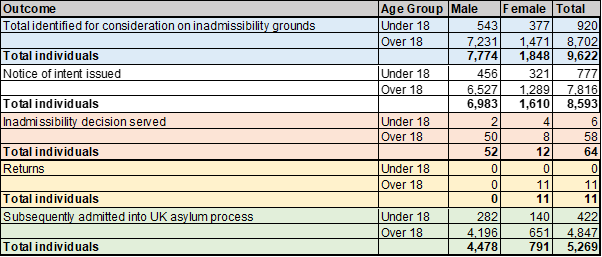

Home Office data obtained through a Freedom of Information (FOI) request suggest that hundreds of children and families have already been served with ‘notices of intent’ informing the claimant that their claim is being considered as inadmissible. The provisional data in Figure 3 shows that in 2021, 920 children – 10% of all those affected – were identified on inadmissibility grounds and 777 were issued with a ‘notice of intent’. At the time this data was generated, 422 children (46%) had subsequently been admitted in the UK asylum process.

Figure 3: Inadmissibility Process outcomes in 2021 for children and adults. This is provisional data provided by the Home Office via a FOI response.

More recent figures show a similar pattern, leading to the conclusion that the inadmissibility rules have in effect resulted in adding a further six-month delay to families’ claims. The length of time that families are living in insecurity is significant, especially for children who are spending their crucial formative years in deep poverty and with limited opportunities for integration and development.

The Home Secretary wants to be honest with the public. Part of this also means being honest about the faces behind the numbers, including the children and families seeking protection in the UK. Analysis shows that children and adult family members make up two-thirds of those receiving Asylum Support, therefore placement planning and policy interventions need to take account of these realities. The increasing reliance on immigration detention as well as unsafe, temporary accommodation, prolonged time spent barred from the labour market and living in deep poverty on Asylum Support all have negative consequences for children’s welfare. These are complex challenges which have no easy solutions, but we must do better to properly safeguard and promote the welfare of children in the asylum system.