Net migration into the UK was 504,000 between June 2021 and June 2022, far higher than the previous record of 330,00. While the single biggest factor behind the rise in net migration was the new visas open to Ukrainians and BN(O) passport-holders from Hong Kong, it is the increase in the numbers coming to the UK on student visas that is the potential target of a government crackdown. Alan Manning argues that further research in this area is urgently needed.

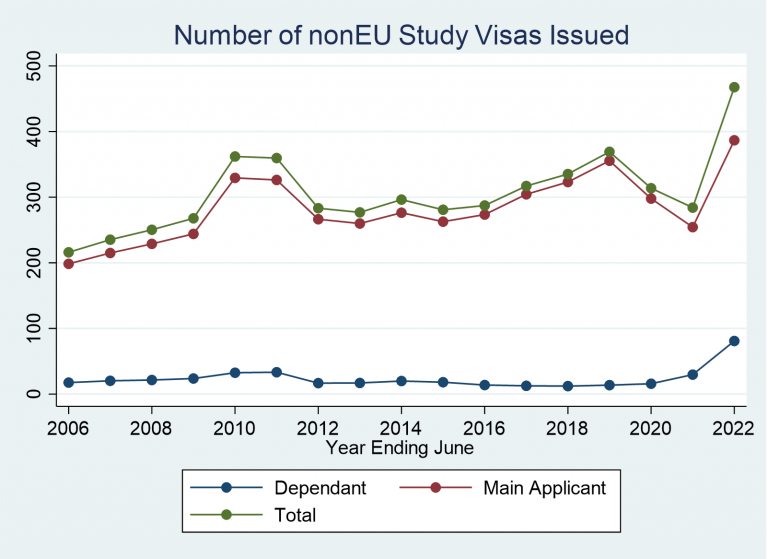

The number of study visas issued to non-EU citizens, both main applicants and dependants over the last 15 years has hit a record high, as shown by the graph below. The rise in the number of dependants is also very striking (now accounting for 17 per cent of all visas when it was previously less than 5 per cent).

This rise has been faster than anticipated. As a result, the government has hit its 2030 target for the number of international students in its International Education Strategy 10 years early.

Behind the numbers

It is likely that much of the recent rapid increase is the result of the introduction of the Graduate Visa launched in July 2021 that grants graduates of UK institutions and their dependants at least two years of unrestricted work rights in the UK. A post-study work visa has existed in some form since 2004 and in 2011 just over 40,000 such visas were granted, but that route was closed to most graduates in 2012. In contrast, in the year ending in September 2022 there were over 70,000 Graduate Visas granted and this number is likely to increase.

A government talking about the desire to reduce net migration but presiding over record high migration is now reported to be planning a clampdown on student visas. But for those in higher education and their supporters, any such plans are derided as mindless. Instead, the growth in numbers can only be a cause for celebration – a rare example of a part of the UK economy that can be regarded as world-class, a major source of export earnings, an important source of funding for educating domestic students and research, and a contribution to the levelling-up agenda given that universities are spread throughout the UK. All of these claims are true but there remain some causes for concern about the way in which student numbers have increased.

An arbitrary cap on the number of international students, motivated by a desire to limit the headline net migration figures, is a bad idea. Instead, it is essential to understand what lies behind those numbers. If student numbers are increasing, then net migration will temporarily increase but the long-run effect will be much smaller. In the past when there was a post-study work route, about 20 per cent of international students stayed long-term, so that if there were 500,000 visas issued a year, this would contribute about 100,000 per annum to net migration – not nothing but much lower than the current headline figures.

One reason that international students are attracted to the UK is the world-class education they can find in many institutions. However, it is important to realise universities are not just selling an education, they are also selling an opportunity to work in the UK. This was the case to a lesser extent prior to the Graduate Visa (when graduates had to find an employer willing to sponsor a work permit) but the balance needs to be right.

A worthwhile investment for the right to work in the UK

The Graduate Visa creates demand for UK degrees just for the work rights even if the qualifications themselves are worthless. A student can work 20 hours a week during term time and full time throughout the holidays (approximately 70 per cent of each study year) and then full time post-study for at least two years. This means enrolling on a one-year programme provides the opportunity to earn at least £50,000 in the UK even if the graduate only earns the minimum wage. Compare that with tuition fees of £13,000 and about £3,000 in visa fees/charges and it can be an attractive proposition for some international students.

If the work rights are a major driver of increased student numbers, we would expect to see faster growth in students from lower-income countries for whom even a minimum wage in the UK is likely to be attractive in comparison to salaries at home, particularly among those with dependants (as the dependants can also work, more than doubling potential earnings). And that is exactly what we see.

So universities are not just selling education but also, in part, work permits. A scheme that gave work rights for stays in UK hotels would be out of the question, but in the context of universities an equivalent scheme is regarded as common sense by many.

There are two reasons for this. First, the money from the international students pays for the education of domestic students and, more importantly, research. Universities are of strategic importance to the economy in a way that Blackpool guest houses are, with all due respect, not. But this is a very indirect way of funding research because most of the extra students are likely to go to less research-intensive institutions. An alternative would be for the government to sell work permits directly and then use the proceeds to fund the research deemed most important.

Why questioning assumptions is crucial

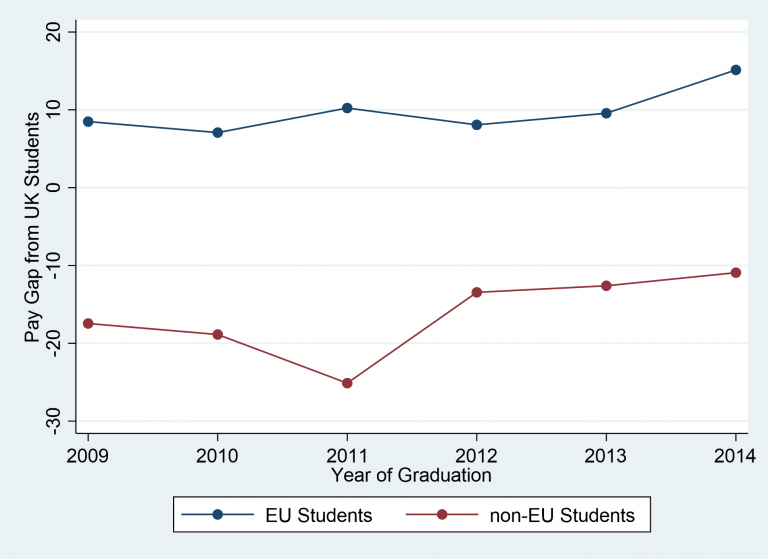

Another common argument for the Graduate Visa is that graduates are highly skilled, exactly the type of talented people we are looking to attract to the UK through other work visas. Many graduates are talented but there is evidence that there is a tail that is not, and there is some evidence of exploitation and of students switching to work visas to work in low-paid social care. The graph below presents data from the Longitudinal Education Outcomes statistics on the lower-quartile earnings of Master's graduates from European Union (EU) and non-EU countries relative to UK graduates, five years after graduation.

UK and non-UK post-graduation earnings compared

EU Graduates have always earned about 10 per cent more than UK graduates but non-EU graduates earn 10 per cent less (the gap was 20 per cent at the time of the post-study work visa prior to 2012). And the level of these earnings is low; £21,200 in 2019 for the 2014 cohort, not much above minimum wage and below the lower quartile for non-EU students with undergraduate degrees even though the qualification is meant to be more advanced (a pattern not seen for EU and UK students).

Some of this evidence has been available for a long time. I was chair of the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) when it produced a report in 2018 on international students. While generally very supportive of international students, we were concerned that many supposedly highly skilled graduates went on to have very low earnings. We recommended more research to understand the reasons for this before re-introducing a post-study work visa; the HE sector and the Department for Education saw no reason to delay.

The latest data has done nothing to change my mind. It is not that that I definitely think change to post-study work rights is needed. Yet there is evidently some cause for concern and it would be wise to investigate further.

There are more general points here about immigration policy. Business groups (including HE) lobby for more liberal immigration policies that would benefit their sector but almost always use arguments and questionable research showing that this change will benefit the economy and society as a whole and often denigrate scepticism as mindless or rooted in prejudice. There is nothing wrong with lobbying; it is important to hear what business thinks and the problems it faces. Often what is best for business is best for Britain but not always, so it is best to consider all claims with a critical eye. One reason this is important is that public confidence in the immigration system is undermined when there is a gap between rhetoric and reality eg, the evidence for the claim that all graduates are very talented. Business often portrays itself as the victim of public scepticism about the benefits of immigration but perhaps it has sometimes been the architect of it.